Burning Desire

The Jimi Hendrix Experience

Copyright 12-25-22 / 1,900 words

by Jon Kramer

Nonfiction

I’ve lived – more-or-less – in Monterey, California since the mid 1990’s when I decided I’d had enough of not surfing. I didn’t end up here because of the music scene, although there is some serious legendary music history here, some of which we’ll get into in a moment. I came for many reasons, but the original one was the surf. The waves here are various and plentiful, and I wanted to learn surfing – to become a surfer – and I was dead serious about it. But that’s a whole nother story, or book, or podcast series. The point is I landed in Monterey. Good for me.

Through the ages, the Monterey Peninsula has been a seminal turning point in many lives. People of all walks – priests, sailors, authors, artists, scientists, performers, business people, golfers, politicians, doctors, lawyers, and countless others – have come and been changed by the unique magic of this young, vibrant, and rugged coast. There is no shortage of historical figures who landed here – with or without intention – and experienced events and epiphanies that changed their life and that of many others. The environment is forcefully dynamic – you cannot reside here and live passively. It is, in a word, thrilling.

Through the ages, the Monterey Peninsula has been a seminal turning point in many lives. People of all walks – priests, sailors, authors, artists, scientists, performers, business people, golfers, politicians, doctors, lawyers, and countless others – have come and been changed by the unique magic of this young, vibrant, and rugged coast. There is no shortage of historical figures who landed here – with or without intention – and experienced events and epiphanies that changed their life and that of many others. The environment is forcefully dynamic – you cannot reside here and live passively. It is, in a word, thrilling.

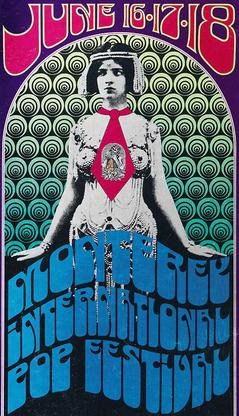

If you’ve heard anything about music history on the Peninsula, you’ve likely heard of the Monterey International Pop Festival which took place June 16 – 18, 1967. The “Festival” turned out to be one of the great landmarks of Rock and Roll although no one would have predicted that at the time. It’s especially remembered for the first major American appearances by the Who, Ravi Shankar, and Jimi Hendrix. It was also the first large-scale public performance of Janis Joplin and the introduction of Otis Redding to the world.

The Festival featured many of the era’s bedrock bands and most of the up-and-coming. It’s now considered an event on par with Woodstock, which took place two years later and featured many of the same artists. However, by virtue of its groundbreaking avant-garde approach to popular music, I – and many others – would argue that Monterey International Pop Festival was more important than Woodstock. This, despite the fact Woodstock – at 500,000 attendees – was nearly ten times as big. Supporting this premise, several well-known performers declined invitations to Woodstock for the very reason they felt it would be a “second-rate Monterey Pop”.

The idea of a “Pop Festival” grew organically from a group of friends. John Phillips (of the Mammas & the Pappas), Alan Pariser (a whirling dervish of music promotion), record producer Lou Adler, and publicist Derek Taylor were shooting the breeze one day, griping about how Rock and Roll got no respect. It was 1967 for Chrissakes, and Rock was damn-well established! But the Establishment still viewed it as an anomaly. Phillips and company decided to do something about it and a “music festival” seemed like a good idea. It would storm the gates and put Rock on par with jazz, blues, classical, and all the other accepted musical genres. Since Monterey was already known for its Jazz Festival and the Big Sur Folk Festival, they decided that was the place to hold it. That, and the fact the fairgrounds in Monterey had nothing going on at the time and was fairly inexpensive.

The whole concept was put together in less than two months. Phillips wrote a song to promote the event. Listen here: “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers inYour Hair)” Sung by Scott McKenzie and released in May of ’67, it became an instant huge hit just prior to the Festival. Magazine and newspaper ads helped fill the venue to bursting: the arena housing the stage had a seating capacity of only 7,000, but it’s estimated at least 9,000 people crammed into it, many of which were standing in the aisles and stairs. At any given time 20,000 more milled around outside.

Initially the organizers planned to pay all 33 performers. But that quickly became problematic considering ever-mounting expenses. So, they pivoted and made the Festival into a charity event, providing the artists first class travel and accommodations but no payment for their performance. Interestingly, the only musician to get paid was Ravi Shankar ($3,000) for his afternoon of sitar playing. How that happened is lost in the pot smoke of history, but it certainly worked out for the famous sitar virtuoso.

Initially the organizers planned to pay all 33 performers. But that quickly became problematic considering ever-mounting expenses. So, they pivoted and made the Festival into a charity event, providing the artists first class travel and accommodations but no payment for their performance. Interestingly, the only musician to get paid was Ravi Shankar ($3,000) for his afternoon of sitar playing. How that happened is lost in the pot smoke of history, but it certainly worked out for the famous sitar virtuoso.

Hendrix’s appearance was not originally in the cards. Although popular in Europe, Hendrix was not on the American music radar. Event organizers wrote him off before he was even mentioned. But in a stroke of good luck, Paul McCartney (yes, THAT Paul McCartney)– who considered Hendrix “An absolute ace on the guitar!” – was asked to join the Festival board. Upon reviewing the invitees, however, McCartney insisted the event would be incomplete without Hendrix. He then went even further, stipulating that he would join the organization only on the condition that the Jimi Hendrix Experience perform at the Festival. The Festival organizers were no fools – you don’t say no to such a request by Paul McCartney, especially if you want him on your board. Thus, history was made and, in the end, featured a burning guitar.

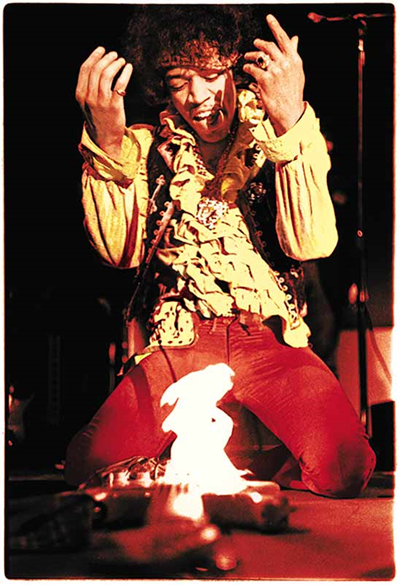

The Jimi Hendrix Experience was one of the Festival’s final acts – taking the stage on the evening of Sunday, June 18, just after the Grateful Dead and before the closing act of the Mammas and the Pappas. Hendrix was introduced by Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones (the Stones did not play at the Festival) as “The most exciting performer I’ve ever heard!”.  Hendrix hit the ground running with hell-on-fire volume and dive-bombing feedback and reverb. He never slowed down. He grabbed the vibrato bar on his guitar and throttled it like a stick shift on a rocket ship, blasting the acoustics into the crowd like a cannon shot. It was the first time an American audience had ever heard such heavy-hitting acoustic assault and it heralded the dawning of a music revolution. Hendrix ended his performance with a super-charged version of “Wild Thing”, at the end of which he dropped his guitar onto the stage, knelt over it, and set it on fire.

Hendrix hit the ground running with hell-on-fire volume and dive-bombing feedback and reverb. He never slowed down. He grabbed the vibrato bar on his guitar and throttled it like a stick shift on a rocket ship, blasting the acoustics into the crowd like a cannon shot. It was the first time an American audience had ever heard such heavy-hitting acoustic assault and it heralded the dawning of a music revolution. Hendrix ended his performance with a super-charged version of “Wild Thing”, at the end of which he dropped his guitar onto the stage, knelt over it, and set it on fire.

In one of those simple twists of fate, standing in the front row of the audience was a 17 year old kid named Ed Caraeff who was, in the parlance of the times, a “camera buff”. Caraeff had no idea who Hendrix was and had never heard his music. But he was front and center with a camera. After three days of shooting, however, he was running low on film. He had only a few shots left on the roll and he took them of Hendrix burning his guitar. His shot (below) made history and has become one of the most iconic images in Rock and Roll. Caraeff was, at that very moment, launched into a wildly successful career as a photographer and graphic designer. He went on to photograph and design more than 400 record album covers. His work has been inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Back to the pyre: As the fire dwindled, Hendrix picked up his guitar again and smashed it to bits on stage. He then threw the pieces into the crowd. But it wasn’t just the burning that got noticed. His music AND his performance at Monterey International Pop Festival was the talk of music critics across the country. Jimi Hendrix had arrived in America, and he took the music scene by storm.

Three brief years later, James Marshall (Jimi) Hendrix – arguably the greatest electric guitarist ever to pick up the instrument – died of a drug overdose. He was only 27.

****************************************

AFTER WORDS

I loved Hendrix’s music and the man who created it. There were times when my siblings got sick of me playing his tunes over and over. To hear the last cords of “The Wind Cries Mary”, for example, I’d rewind the tape again and again and again until I fell asleep to those fantastic, haunting, final notes. Sadly, while I was obsessed with his music, I never got to see Hendrix play in person, much less meet the man himself. But my older brother Mike did, and here’s him telling it:

“Yes, I did meet and talk with Jimi Hendrix. It was on August 9, 1967 at the Ambassador Theater in Washington, DC. I was 15. The Ambassador was a movie theater converted into a music venue. They tore all the seats out and if you wanted to sit down, you could do so on the concrete floor. Anyway, I knew Hendrix was coming to the Ambassador and I had heard a couple of his songs on the radio and wanted to see him in person. Although he was a hit in England, he was not yet very well known in the US and his album had not yet come out here. (It came out the end of August.) I didn’t even know what he looked like!

I took the bus from near Halpine View (where we lived) down to Adams Morgan and gained free entry to the Ambassador because I volunteered there to distribute fliers and posters for their various shows. ( I wish I had kept a copy of all the posters I put up and distributed…grrr.)

After my free entry, I’m sitting on the floor watching the opening act – The Strawberry Alarm Clock – from Baltimore. They had one hit, “Barefoot in Baltimore” but were actually not very memorable. Anyway, there was a cool looking Black guy – some years older than me – with an Afro sitting with his two white friends next to me on the floor. He was wearing the greatest shirt – it had these two big eyes on it. It was really pretty striking. I turned to him and said,

Hey, how you doing?

Cool, he said. And you? You digging’ it?

It’s alright, I replied, but I came to see Hendrix!

Me too, he said.

That’s a really cool shirt you have on. Where did you get it?

In London, man.

Right on, I replied.

I wondered how this cat managed a London trip. As it happened, his buddies looked sorta English. Maybe that was the connection? Anyway, a little while later, as the opening act was winding down, he and his two buds got up to take a break.

I’ll see you later, man. he said, as they headed toward the side door.

Yeah, cool, I replied, figuring they would be back for the main act.

Finally, the curtain closed on the Alarm Clock – their time was up. I looked around, anticipating the Main Event and expecting to see the Black guy and his friends come back in for the start. But they were gone. They never did come back – at least not to where I was sitting.

Fifteen minutes later, the curtain opens to the beginning of “Purple Haze” and who’s playing, but the guy with the coolest shirt on – Jimi Hendrix! It turned out his friends were Noel Redding and Mitch Mitchell, the other two members of the Jimi Hendrix Experience. It blew my mind! He played for the next 4 nights, and I took the bus down every day to see him! And I saw him every time I could after that. He was truly unbelievable!

And the shirt he was wearing that first night was the very same one he is wearing on the cover of his first album, “Are You Experienced”. Look closely and you can see the eyes.”