Copyright 10-24-22 / 2,700 words

by Jon Kramer

Nonfiction.

The Left Eye

Even though it happened to both of us in the same way and in nearly the same place, and despite the fact this is my writing – not his – it happened to the Pirate first, and it happened to the Pirate worse. And since the Pirate is far more famous than me, I’ll begin this with his story.

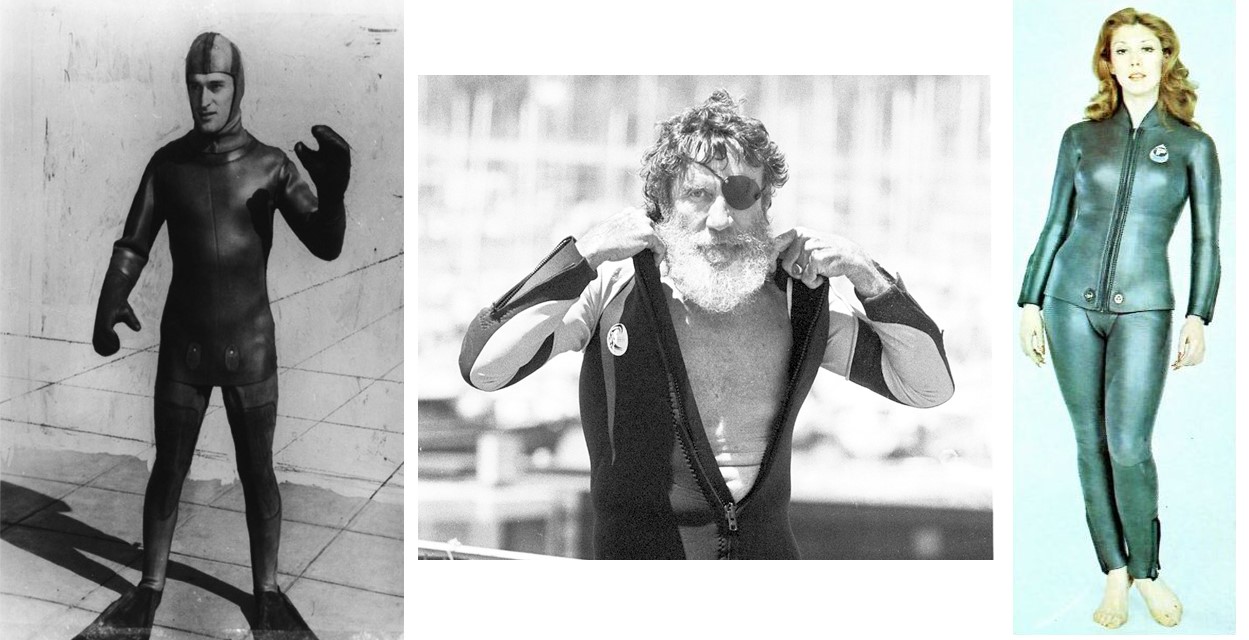

When Jack O’Neill returned to California from WWII, he got into surfing in a big way. Before he went to war, he was keen on bodysurfing. But when he came back, he really got into surfing atop boards – so much so that he decided he would make it his business. He opened his first surf shop in San Francisco in 1952. Later he moved his operation down the coast to Santa Cruz, a smaller town with better waves. There was just one problem – the water temperature rarely gets above 55 degrees – even in summer – and that seriously limited the time you could spend in the water.

Jack went to work. In the Navy he’d learned about insulative properties of neoprene and began experimenting with making it into garments that could be worn in the water. Although he wasn’t the first to invent the “wetsuit”, he quickly became the Henry Ford of wetsuit manufacturing. His motto: “It’s Always Summer on the Inside” made the wetsuit an instant success. O’Neill produced wetsuits for the masses, and the masses took to the water like never before.

In short order O’Neill created and dominated the world wetsuit market. He initially made wetsuits for men but saw the obvious potential of an added line for women. Then he added a kids line. Then gloves and booties. Then rash guards. And then every other apparel thing he could think of. Jack O’Neill became a multimillionaire back when a million bucks actually was something.

O’Neill was always tinkering – improving his products and experimenting with all things aquatic. He made apparel, he made surfboards, he made boats. Many in his family followed his lead. His son Pat is credited with creating the modern surfboard leash – a now-ubiquitous cord that connects one’s leg to the back end of the board. It serves a very convenient function of being able to immediately retrieve your board after a wipeout. Even more vital is the fact it prevents boards from flying around loose in the surf. As a result, it’s safe to say the surf leash has helped avoid an untold number of accidents and very likely has saved lives. But it hasn’t been without consequences.

During the experimental phase of surf leash construction – the early 1970s – the cords were either too long, too short, too heavy, too light, too stretchy, or too unforgiving. It took awhile before the right balance of material and resilience was reached. As is often the case, trial and error dictated the progress. But sometimes the error part takes over like a monster in a Sunday matinee.

One afternoon in 1972, Jack was out surfing with friends and was wearing the latest version of his son’s leash. At the time there was great debate in the surf community: To leash, or not to leash? Purists considered it “cheating” and labeled it an abomination. Progressives were happy to have significantly more board time by not having to swim for their boards after a wipeout. And those that couldn’t surf proficiently or swim very well grabbed onto the leash and never let go.

While Jack, of course, promoted the idea and his son’s invention, he wasn’t pushy about it. For the most part he stayed above the fray. But he was well respected so his influence undoubtedly jumpstarted the leash revolution. The fact he wore a leash was evidence that a shrewd mind considered it worthwhile.

A wave came and Jack jumped on it. Things were cooking along pretty nicely until an unpredictable rough section caused him to fall off his board. He landed in the whitewash of the crashing wave. Initially he was pulled under but easily regained the surface on the backside of the wave. His board, meanwhile, was still caught in the jaws of the wave and was pulled toward shore. His leash stretched to its limit quickly. When the wave finally released the board, it recoiled like a sling-shot, snapping back and smashing into Jack’s face.

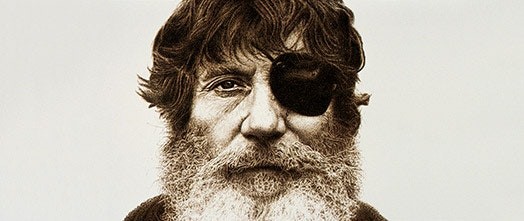

There was no saving the eye. But Jack – being Jack O’Neill – used the incident to his advantage and began playing up the public image of a renegade scofflaw, complete with sinister grimace, cocky eyepatch, and scraggly beard. He became Santa Cruz’s official, unofficial living Pirate. He didn’t care what people thought about his appearance – it worked for him, and it certainly helped the business.

Even after losing his eye, Jack continued to promote his son’s leash concept. It gradually caught on and is now considered essential equipment in surfing. These days NOT having a leash is scorned when there are a lot of people in the lineup.

The Right Eye

In April 2014 there were reports of a guy who looked a bit like Frankenstein terrorizing the Central California coast. It was not, as some suspected, the Pirate. This was confirmed by more than one person who knew the Pirate, his habits and whereabouts at the time. And, it was noted, the Frankenstein guy had his gnarly scar and eye patch on the right eye.

My friend Ignacio and I have our birthdays in early April and we use it as an excuse to blow town for a day, surfing up or down the coast. That particular year we noticed the surf reports suggested a decent swell would hit Santa Cruz on the 5th. So, along with our friend Tim, we loaded our boards and took off for Steamer Lane. We got there in time to score a prime parking spot overlooking the main break. We gazed over the cliff: the waves were fantastic.

The outside reefs were periodically serving up ten-foot faces with perfect curling peaks that offered some folks the rides of their life. We all caught our share, a few of which were epic memories. After a couple hours, Tim and Ignacio drifted back toward the quieter, more predictable waves of Cowells which, on a day like this, provides nice long rides down the line. I wanted just one more supercharged ride before joining them to wind up the day with some easy, mellow waves.

A nice set was marching in. Me and about 50 other people raced toward it. I managed to position myself just right and when it started to break, I went for it. The wind howled up the face showering spray over the top as I popped to my feet. To make such a wave you need to stay low and shift your weight forward on the board, least the wind stall you out. I was tightly crouched like a jockey. I’d just started the ride, accelerating down the face, when I saw three surfers below, right in my direct path. They had a look of terror in their eyes. I reflexively jumped to the back of my board. The nose raised up and, in an instant, the wind caught it, stopping me dead in my tracks. I’d averted a serious collision, but was thoroughly frustrated – it would have been a great ride.

I decided to move away from the crowd and paddled over to a more lonely spot where I would sometimes sit when conditions are just right. It’s a place where the peaks form only on the largest sets at a certain angle. The wave at this particular spot doesn’t break often, so most surfers don’t waste their time waiting here. But I had a hunch it would break here at some point on the rising tide today. All things come to he who waits….

Sooner than later a set appeared that looked like it had potential. I could see from my perch there were four to five waves forming a freight train on the horizon. The first two stood a little higher than the others as they marched directly toward my position. If it hit near me, I decided, the second wave was the one to go for. With luck it would carry me all the way back to Ignacio and Tim, some 300 yards distant. I smiled at the prospect of pulling off the wave and landing right next to them.

The first wave jacked up and thundered through. Sure enough, it formed a peak near where I sat. I should have gone for it – no one else was even close – and it went by unridden. Unfortunately, that wave served as a clarion call: The whole crowd started paddling furiously toward me and the now-obvious takeoff spot I was occupying.

I was ready and in perfect position for the second wave. As it crested, I paddled hard, popped up on the board, curled into a tight ball, and dropped down the face. After I made the drop, as the board picked up speed and stabilized, I brought the craft into trim along the face of the wave. I floated along, right on the edge of the curl. It was screaming fast – the board was humming over the wave surface. It was a perfect wave… just what I wanted.

Very soon, however, a potential problem presented itself. So many surfers were now in my path that I had to make split-second maneuvers to avoid them. As I zoomed along the breaking wave, I zig-zagged through the bodies and boards and managed navigating through the initial gauntlet. The wave was jacking higher and faster, but I was in good position and stayed right with her. I faded back a little to get deeper into the curl, then blasted forward, carving along the face.

Suddenly – there is nothing but suddenly in these cases! – there appeared another surfer paddling directly across my path. In such a predicament you have two choices: cut low to go behind them, or ride high to get around their front. Going low was not an option here – there was another surfer behind him. I chose the high road.

Just at the critical moment, however, the other guy made a miscalculation: He thought I would go behind him and, in an effort to help me avoid him, sprinted as fast as he could up the wave. But by doing so, it placed us squarely on a collision course. The clock ran out.

It happened in an instant. In an effort to avoid plowing my surfboard into his head, I pivoted hard right and stepped off the back. The board rocketed over the wave past him – just barely – and sent me sailing through the air. I crashed right on top of him and the ensuing entanglement tied us together. Then the wave crashed on top, engulfing us both in the falls. The force squashed us like bugs in a flyswatter, smashing us down underwater, all the way to the seafloor.

Although I had no idea of it at the time, my board was ripped right off my leash and launching 20′ into the air before sailing back to Earth. The next wave carried it into the rocks along the cliff. I was too busy being mauled by the wave to know any of this.

The two of us, manacled together under the sea, desperately clawed and struggled for the surface. I managed to poke my head above the whitewater first and had just started sucking in oxygen when I was suddenly karate-chopped by a terrific force that hit my right eye and snapped my head back, knocking me silly. The lights went out and my mind went black. A crimson shower of blood washed over my head. The sea spread red foam around me.

It was a surfboard – his surfboard – that did the damage. My partner in doom was yet underwater and still had his leash attached to his leg, causing his board to spin wildly on the surface, like a helicopter blade run amok. When I got to the surface it smashed full force into my right eye. The disaster was further advanced by two more huge waves crushing us as I tried to extricate myself from his board and leash. Finally, after a third thrashing, there was a lull.

I had come back into consciousness when the second wave hit, spitting water as well as blood. The two of us were tangled together by our leashes, but in the lull before the next set he managed to quickly untie the Gordian Knot and released us from bondage. Then he looked at me and yelled:

Dude – you’re hurt, bad! We gotta get you to the beach NOW! He was really excited. Get on my board. Let’s go! But he had a shortboard, barely 6 feet long. Not knowing the full reality of the situation, I protested, announcing that I’d get on my board – it was two feet longer and would float me better. “YOU DON’T HAVE A BOARD!” he yelled, “IT’S GONE! Get on mine – hold pressure on your eye – we gotta get you to the hospital”.

His name was Tom. He paddled like hell and got me to shore on his board. I stumbled onto the rocks and clawed myself up onto land while holding my eye. Several people came running down from above and helped me up the cliff. A gal that saw my board flying free had come down to the rocks and rescued it. There quickly formed a buzz of excited, concerned people around me. Several offered help. Many wanted to call 911. Others offered to drive me to the hospital.

Someone produced clean tissue and helped staunch the bleeding. Another guy had a first aid kit and got some gauze and antibiotic. A few folks helped doctor me and, after awhile, the bleeding slowed dramatically to where I could inspect the damage. It was a seriously bad cut – deep lacerations both above and below the eye, needing several stitches for sure…. But the good news was I did not feel my eye coming out of its socket and I could still see hazily out of it, though by now it was swelling shut.

Some of the group offered to paddle out to find Ignacio and Tim and tell them what had happened. They asked me for a description: Two guys about 6 feet tall, with long boards and wearing black wetsuits, I said. “Oh, yeah, Tom quipped, THAT narrows it down!” Everyone laughed – there were probably 100 people out surfing described that way.

I got to the hospital and an ER doc with hands as big as Godzilla did a masterful job of sewing it all back together. Twelve stitches outside – both upper and lower eyelid and three stitches inside the lower eyelid (never knew they could do that). Orbit cracked but thankfully intact. The eye itself was badly bruised but eventually healed just fine. My friends all said it was too bad the incident had not happened in time for Halloween – the swelling and stitches gave me the look of Frankenstein.

I got to the hospital and an ER doc with hands as big as Godzilla did a masterful job of sewing it all back together. Twelve stitches outside – both upper and lower eyelid and three stitches inside the lower eyelid (never knew they could do that). Orbit cracked but thankfully intact. The eye itself was badly bruised but eventually healed just fine. My friends all said it was too bad the incident had not happened in time for Halloween – the swelling and stitches gave me the look of Frankenstein.

It took a few months, but the healing went well and now you can hardly see the scar. I must admit I miss the zig-zag stitching and the Frankenstein wound. Some of the overt stares it garnered on the street were memorable. But while my Frankenstein fame was short lived, I’m perfectly OK with not having a permanent head injury or lost eye.

While I did wear an eye patch for a few weeks, I missed my chance to join Jack O’Neill as a scary surfing buccaneer. In fact, though I surfed in front of his house on a regular basis, I never did meet the old Pirate. Sadly, a few years later – in June, 2017 – the Pirate of Santa Cruz surfed off into his final sunset. He was 94.